Would you like to see a menu?

By Lynne Prunskus

Would you like to see

a menu?

By Lynne Prunskus

Have you ever wondered what our local restaurants were serving in the 1800s? In the mid-1800s, hotels such as the Prospect, Table Rock House, the Brunswick Hotel, and the Museum Hotel emerged in the vicinity of what is now Queen Victoria Park in Niagara Falls. But it was the Clifton House, built in 1833 at the head of the Ferry Road (Clifton Hill) on the modern site of Oakes Garden Theatre, that became the premier hotel of the day, and held that status for more than 50 years.

The Clifton House catered to the rich and received many famous visitors in its day, including the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) in 1860. Singer Jenny Lind entertained guests in the extravagant Concert Hall located in the courtyard. The Concert Hall was added when Samuel Zimmerman, a wealthy banker and benefactor of Niagara Falls, owned the hotel. The hotel even had its own signature music, The Clifton House Polka, written in 1852 by a man named Poppenburg. Proprietors, D.H. Bromley & Co. ran the Clifton House in 1865. The reputation of this fine hotel lives on through the advertising of the period promoting the Clifton House as a hotel “celebrated for its quiet elegance and features of comfort and convenience…the cuisine service and attendance superior in all respects.”

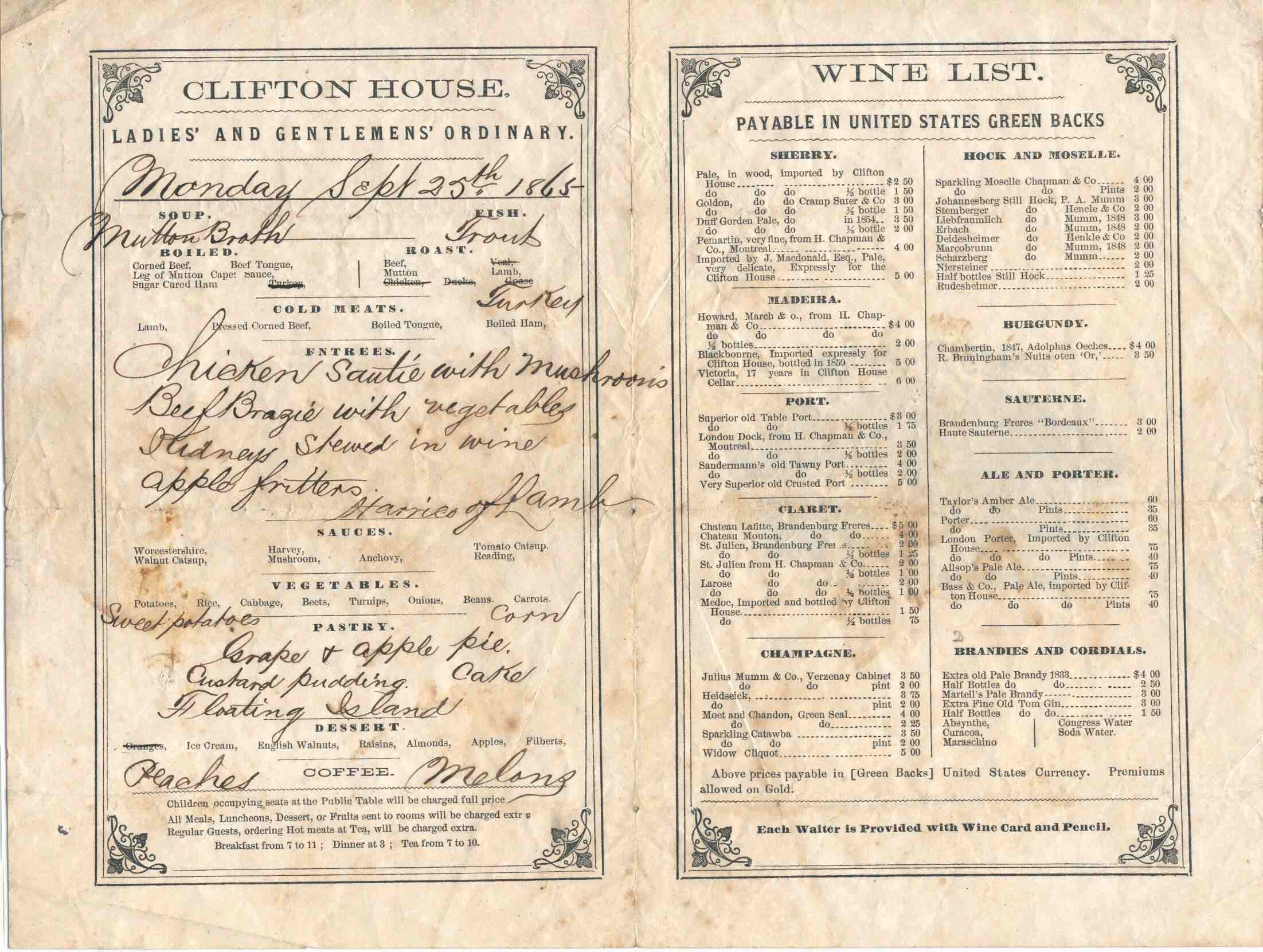

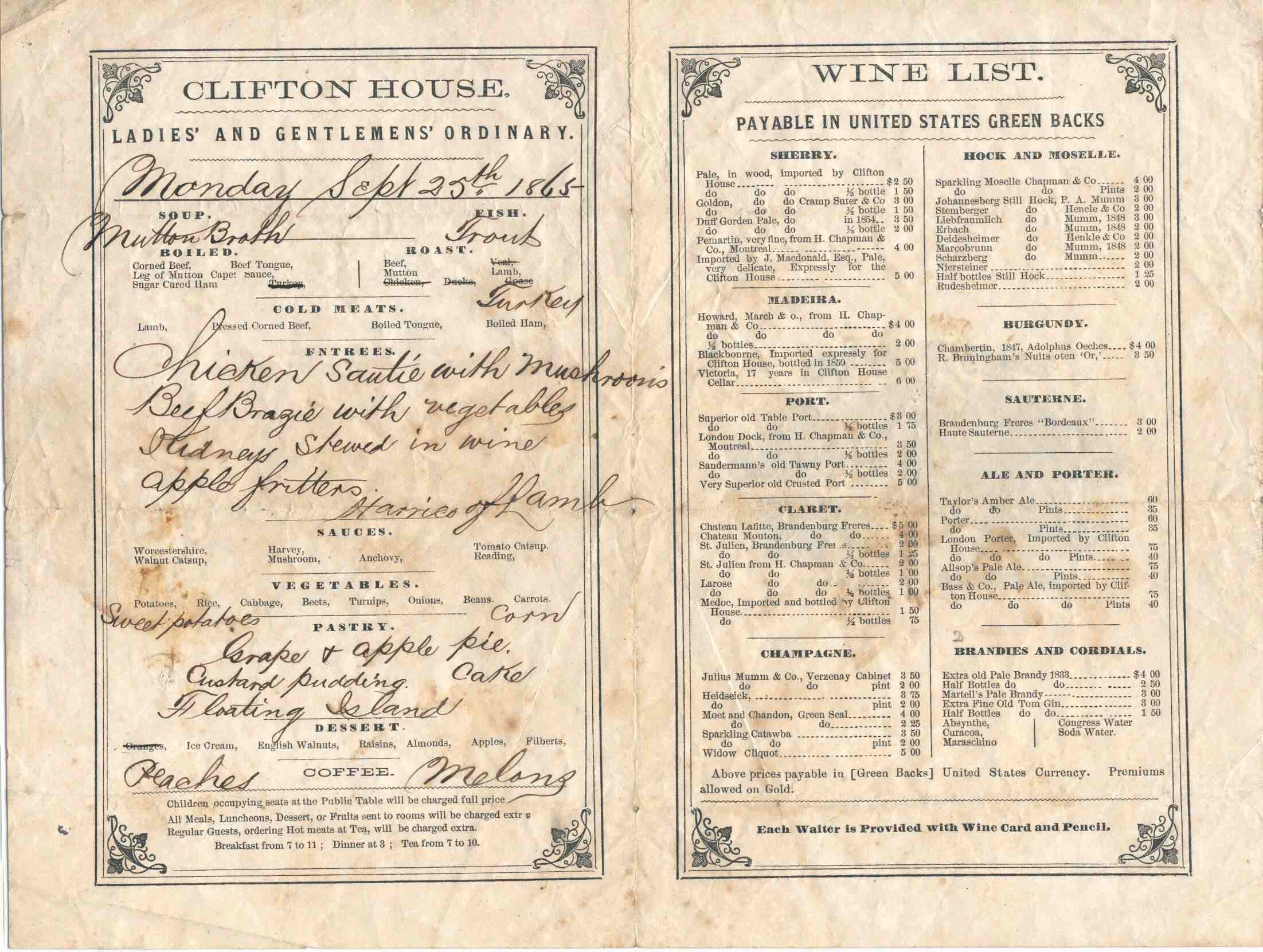

An original restaurant menu from that period reveals much about the times. It also does an excellent job of documenting our social history by informing us about tastes in food and wine, and indirectly providing clues to social customs, manners, and etiquette. This historical record provides evidence of prices, availability of goods, marketing techniques, and local peculiarities related to lifestyle in a thriving tourist town during the 1860s.

This original pre-confederation menu is printed on a standard 8.5-inch by 11-inch sheet of paper, once white, but now ivory-coloured and mottled with age. Elaborate Victorian ornament decorates the corner of each facing page, with the wine list appearing on the right, and the bill of fare on the left. Handwritten entries in black ink confirm that each daily menu was indeed unique and, aside from the standard goods, all offerings depended entirely on the availability of meat, fresh dairy, and the produce supplied by local distributors. On the back cover of the menu is the logo of the period, a stamped line drawing, complete with fashionable tourists sauntering up and down the walkways and gardens, and stating in print that this was indeed: “Clifton House Niagara Falls – Canada Side.”

On Monday, September 25, 1865, restaurant patrons could choose from five diverse entrées (written in longhand with these unusual spelling conventions): Chicken Sautie with mushrooms, Beef Brazie with vegetables, Kidneys stewed in wine, Apple Fritters, and Harrico of Lamb. Just in case you find yourself wondering what “harrico of lamb” is, the research has already been done. Harrico appears to be a corruption of the old French word halicoter, meaning to cut into tiny morsels—the appropriate preparation for a ragout, or stew—a harrico of lamb.

The oldest recipe for halicot of mutton, from an ancient formula by Taillevent recommends the following procedure: “Put them [the pieces of mutton] all raw to fry in lard, cut into tiny pieces with sliced onions and some beef broth, verjuice, parlsey, hyssop and sage, and boil all together with fine-powdered spices.” Some later English recipes for such a stew call for the addition of white haricot beans, an action that may have resulted from the language shift, since haricot is the French word for bean. Whether or not that is the case, as the word continued to evolve, harrico became the spelling convention adopted by 19th-century English speakers, and the addition of beans became optional.

Apparently the kiddie menu had not yet made its way into the restaurant business. An interesting note at the bottom of the entrée page states that children occupying seats at the “Public Table” will be charged full price. Naturally, this “full price” policy would serve to reduce the number of children making their way to the dining table, and those that did, would presumably be from the well-to-do class of society and accordingly well-mannered.

For the adults, Taylor’s Amber Ale is available for 60 cents, or by the pint for 35 cents. Imported varieties include Bass Pale Ale, Allsop’s, and London Porter, all imported by Clifton House. The wines were various, with Chateau Lafitte selling for $5 a bottle and Chambertin, 1847, Adolphus Oeches burgundy for a mere $4. A number of items on the wine list advertise they are imported (or even bottled) expressly for the Clifton House and one Madeira boasts it has spent 17 years in the Clifton House Cellar.

Never had a Floating Island for dessert? For a perfect finish to a fine dining experience, here is a modern version of this simple, end-of-the-meal indulgence. (Hope you like eggs.)

FLOATING ISLAND

3 eggs

9 egg yolks

1 cup sugar

1 tsp. salt

1/2 gallon

milk

2 tsp.

vanilla

ISLANDS

9 egg whites

1 cup sugar

1 tsp.

cream of tartar

1

tsp. vanilla

Scald milk. Slightly beat 9 egg yolks and 3 eggs. Add sugar and salt to eggs, and then stir egg mixture into scalded milk. Cook custard over low heat until slightly thick (about 1 hour), stirring constantly. Cool and vanilla. Pour custard into shallow pans, filling less than 1 1/2 inches. Prepare islands by beating 9 egg whites until stiff. Add sugar, cream of tartar, and vanilla. Drop islands from a spoon onto custard. Brown islands in oven (350°F) about 10 minutes. Cool and refrigerate two hours. Makes 24 servings. Serve in sauce dishes with two or three islands.

Fire eventually destroyed not only the original Clifton House, but the Clifton Hotel that followed it. The original building was lost in a dramatic blaze on Sunday, June 28, 1898. The fire occurred amid a longstanding dispute over the encroachment of the southeast corner of the hotel onto the roadway, thereby preventing the straightening of the road for the addition of a double railway track. In order to comply with the survey, an expensive renovation would be required—or a long battle in the courts. Destruction by fire ended the dispute.